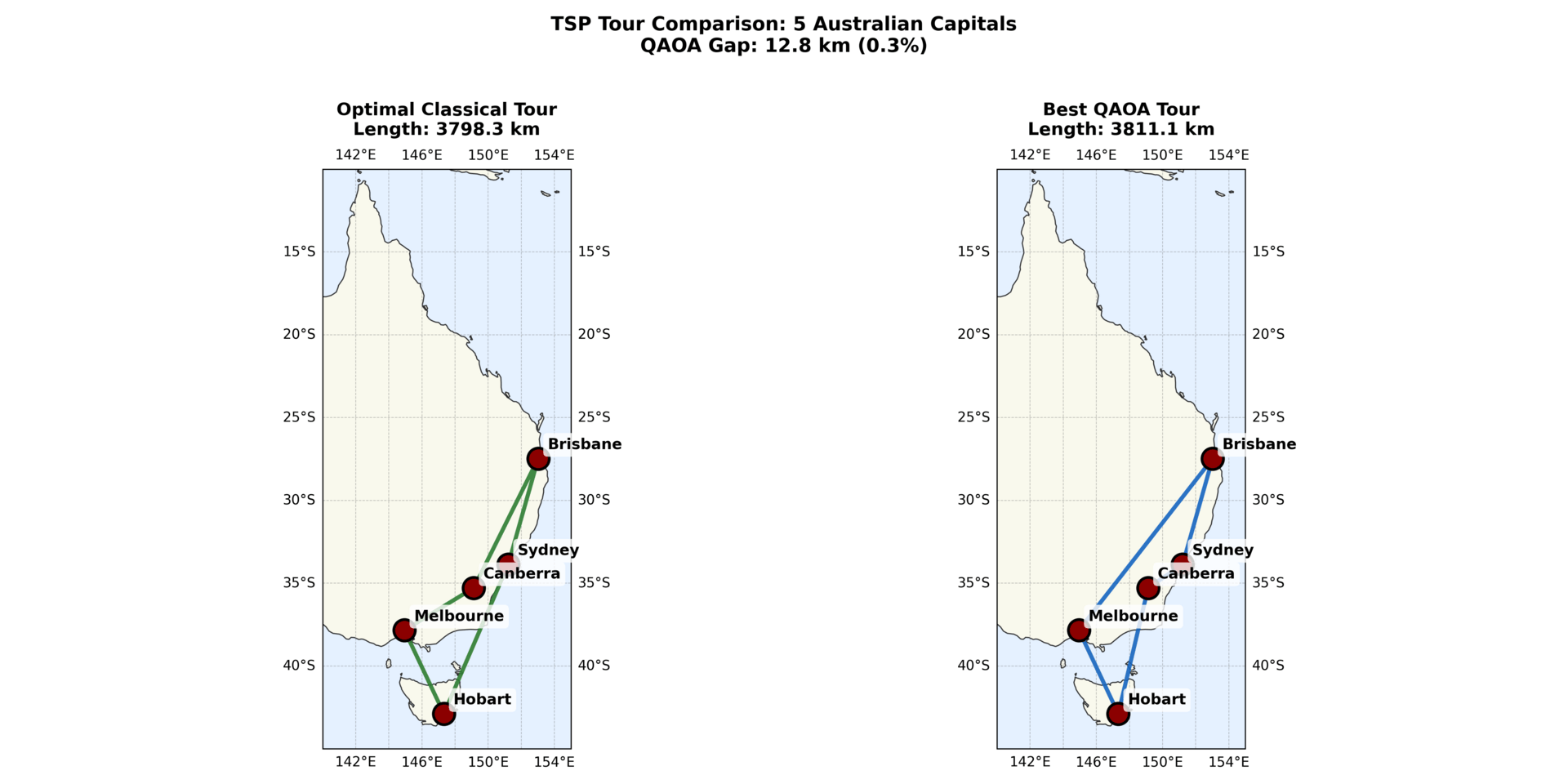

Comparison of the exact classical optimal tour and the best route found using a quantum optimisation pipeline (QAOA) on an Australian TSP instance.

Here’s the TL;DR…

I tested a quantum optimisation approach on the Travelling Salesman Problem using a small experiment I could verify completely. On a five-city instance where I knew the exact best route (3,798.3 km), a hybrid pipeline - where a quantum algorithm generated candidate solutions and classical computation validated and scored them - found a route within 0.3% of optimal.

The experiment did not show that quantum methods outperform classical ones at small scale - they don't. What it did show: quantum optimisation works best as a component within hybrid systems, contributing exploration rather than replacing classical methods. As problems grow too large for exact solutions, how you combine methods matters more than which method you use.

Unfamiliar terms? Jump to the Key Terms section at the end.

Why this experiment exists

Quantum computing discussions often swing between two extremes: either it's portrayed as an imminent revolution, or dismissed as too limited to matter. The reality is more nuanced.

What's actually emerging isn't a replacement for traditional computing, but a new set of tools that work alongside classical methods. Think of it like adding a specialised tool to your toolbox rather than replacing the entire thing.

To understand this better, I ran an experiment using a well-known optimisation problem called the Travelling Salesman Problem.

The Travelling Salesman Problem as a test case

The Travelling Salesman Problem (TSP) sounds straightforward: find the shortest route that visits a set of cities exactly once and returns to the start. Its importance lies in how quickly it becomes hard. The number of possible routes grows factorially (meaning each additional city multiplies the problem size dramatically). With eight cities there are 5,040 possible tours. With 20, the number exceeds 60 trillion. With 25 cities, there are more possible routes than atoms in the observable universe.

I used TSP not to prove that quantum methods are “better”, but because it is a clean way to study how different optimisation approaches behave when embedded in a single pipeline. It exposes the same issues that appear in many operational and organisational problems: sequencing under constraints, trade-offs under uncertainty, and the need to find good solutions quickly rather than perfect ones eventually.

Experimental setup and ground truth

The experiment was designed around three constraints.

Use a deterministic problem - Same inputs always give same outputs, so results are reproducible

Know the exact answer beforehand - By calculating the true optimal solution with classical methods, I could measure how close the quantum approach got

Show all the work - No cherry-picked screenshots or vague claims, just complete, verifiable results

The setup: I started with eight Australian capital cities and calculated distances between them using great-circle geometry (the shortest path along Earth's surface). For cities this small, a classical computer can check all 5,040 possible routes almost instantly.

This leads to the first and most important lesson: if you can solve a problem by brute force, you should. Clever methods aren't better than exhaustive search when exhaustive search is practical.

Making the quantum workflow runnable

Translating TSP into a form quantum computers can work with requires creating a binary variable for every possible assignment: "Is city A in position 1? Position 2?" and so on. Even with shortcuts to reduce redundancy, this creates quantum circuits with many interconnected components.

Simulating these circuits on a classical computer becomes impractical surprisingly quickly. Rather than push forward with something I couldn't properly verify, I reduced the problem size while keeping the method intact.

I narrowed the test to five Australian cities, with Sydney fixed as the starting point. At this scale, finding the optimal route is straightforward: there are only 24 possible tours to check, and the shortest one covers exactly 3,798.3 km.

This smaller instance let me run the complete quantum-classical pipeline while still working with a real geographic routing problem, not an artificial toy example.

QAOA as a generator inside a hybrid pipeline

For the quantum component, I made a key design decision early on. Rather than trying to make the quantum algorithm calculate the shortest route directly, I used it to generate promising candidates that I could then evaluate properly.

Here's how the pipeline worked in practice:

Step 1: generate candidates

I ran a quantum circuit called QAOA (Quantum Approximate Optimisation Algorithm) with different parameter settings. Each run produced a suggested solution.

Step 2: validate and score

Each suggestion was decoded into an actual route. Invalid routes, ones that didn't visit all cities exactly once, were discarded. Valid routes were scored using classical computation to measure their total distance.

Step 3: keep the best

The shortest valid route was retained.

This is what makes it a hybrid pipeline: quantum methods explore the landscape of possible solutions, while classical computation handles the practical work of checking validity and measuring quality.

The results were clear and unsurprising. With just a handful of parameter settings tested, the best route I found was about 10% longer than optimal. When I expanded the search to thirty different parameter settings, the gap dropped to 0.3%, producing a route just 12.8 km longer than the exact shortest path (3,811.1 km vs 3,798.3 km).

This is not surprising. More thorough exploration naturally increases your chances of finding good solutions, just as searching more candidates increases your chances of finding a strong hire.

The important insight is architectural, not algorithmic. This isn't about quantum "beating" classical methods. It's about quantum operating as a component inside a classical system, each doing what it does best. The quantum circuit explores possibilities efficiently, while classical computation handles constraint checking and evaluation where it excels.

Think of it like a kitchen: you wouldn't debate whether a blender is "better than" an oven. You use each tool for its strengths, and the combination produces the result.

Performance improvement with expanded parameter search. The gap between the quantum-generated solution and the known optimal solution decreased from ~10% to 0.3% as more parameter settings were tested, demonstrating that broader exploration produces better results.

What this tells us about scale and cost

For small problems, classical methods win easily. A laptop can check all possible routes faster than simulating a quantum circuit. This isn't surprising or controversial - it's just how things work at this scale.

The interesting question emerges only when exhaustive checking becomes impossible. When you have too many possibilities to check them all, would a quantum-assisted approach produce better candidates than existing shortcuts, given the same time budget?

The answer isn't universal. It depends on the problem's structure, how you encode it, how you handle constraints, and the noise level of the quantum hardware (current quantum computers have error rates that limit what they can do),

What this experiment reveals is where the real computational cost lives: not primarily in the quantum algorithm itself, but in encoding constraints, maintaining validity, and evaluating candidates.

Large, constraint-laden formulations do not make optimisation easier. They move the cost into the landscape and the sampling process.

Why this matters beyond routing problems

Many real-world problems have the same structure as TSP. You're not looking for a single "perfect" answer, but exploring alternatives, testing what's feasible, and understanding trade-offs.

Real-world examples:

Supply chain optimisation: A manufacturer needs to route delivery trucks, but also wants to understand: What if fuel prices spike? What if a key route becomes unavailable? Which delivery deadlines are negotiable?

Workforce scheduling: A hospital assigns nurses to shifts while respecting labour laws, preferences, and coverage requirements. The question isn't just "what's the optimal schedule?" but "how brittle is this schedule?" and "what happens if we change break policies?"

Strategic planning: A company evaluating market entry strategies wants to map out the trade space: Which markets are worth the investment? Which constraints are real barriers vs. artificial ones we've imposed?

In these contexts, optimisation isn't about finding perfection once. It's about mapping out the space of possibilities. The generate-validate-score loop used here applies directly: the value is in structured exploration, not perfect answers.

What this experiment actually showed

This work didn't prove that quantum computers "solve" the Travelling Salesman Problem better than classical computers. Instead, it produced:

A reproducible classical baseline (so we know the right answer)

A quantum-sampling workflow that runs end-to-end

A near-optimal solution (0.3% from optimal) using shallow quantum circuits on a small instance

Clearer understanding of where complexity actually lives in optimisation pipelines

The Pattern: At small scale, brute force wins. At large scale, architecture wins. And the architecture emerging from current research is hybrid - quantum components working inside classical systems, each doing what it does best.

Article setting up this quantum series: Quantum Optimisation Before Quantum Advantage

Articles in the business problem stream:

Articles in the hardware stream:

Key Terms

Travelling Salesman Problem (TSP): A classic optimisation problem: find the shortest route that visits each location exactly once and returns to the start. The number of possible routes grows factorially, making exact solutions infeasible at scale.

QAOA (Quantum Approximate Optimisation Algorithm): A quantum algorithm designed to explore solutions to combinatorial optimisation problems by sampling from a parameterised quantum circuit.

Hybrid Optimisation: An approach that combines quantum and classical computation, using each where it is most effective. For example, quantum methods to generate candidates and classical methods to enforce constraints and evaluate results.

Brute Force: An exact solution method that evaluates every possible option. Practical only for small problem sizes but valuable as a ground-truth baseline.

Candidate Generation: The process of proposing possible solutions for evaluation, rather than attempting to compute an optimal solution directly.

Constraint Handling: The enforcement of rules that define which solutions are valid. In many real-world problems, managing constraints dominates computational cost.

NISQ (Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum): The current era of quantum hardware, characterised by limited qubit counts and significant noise, which constrains circuit depth and reliability.