When making decisions, people usually give equal weight to understanding the problem, its importance, and whether it's doable. But this experiment demonstrates that deliberately giving these factors different amounts of weight works up to four times better.

Here’s the TL;DR…

You can add analysts, streamline approvals, and accelerate delivery, yet still watch work loop back marked “needs clarification.” The problem is not execution capacity. It is a lack of decision convergence.

I modelled a typical six-stage workflow and watched work loop back through the decision stage over and over: not because decisions took too long, but because they didn't resolve the actual question. When I broke "decision" into its real parts: Meaning (what are we building?), Priority (is this worth doing now?), and Feasibility (can we actually do this?), a pattern appeared. These decision types don't commute, and the order and resourcing with which they are applied determines whether work moves forward or just circles back.

I ran 17,600 simulations testing every reasonable way to split up decision-making time and route work through these stages. The balanced approach (equal time for all three) underperformed. Trying to fix just capacity or just process did even worse. The setup that worked: giving 14 units to Meaning, 4 to Priority, and 6 to Feasibility, with specific routing rules produced a fourfold improvement in results.

This is not incremental optimisation. It is structural.

This article isn't about quantum computing or exotic speed-ups (but that does come later). It's about defining your problem properly before you try to optimise anything, and why making decision structure explicit matters more than almost any other change you could make. Quantum methods, if they're useful at all, come last.

Unfamiliar terms? Jump to the Key Terms section at the end.

Most conversations about optimisation start in the wrong place

They begin with tools: better software, automation, or futuristic speed-ups. They assume the hard part is doing the work. In reality, this skips the failure mode that actually ruins outcomes: most organisations can't clearly state what problem they're trying to solve.

The central point of this article is simple: In complex organisations, slow progress comes less from teams working slowly than from decisions that don't stick. Once decision authority gets split up, the system's behaviour becomes unpredictable, and gut-feel fixes reliably fail.

This article focuses on that earlier step. Not quantum advantage, but problem definition before quantum advantage, and why decision structure, not execution speed, is usually what's holding you back.

Why work gets stuck before optimisation even starts

Across government, large companies, and regulated organisations, the same pattern repeats. Work comes in, gets analysed, gets approved, and then comes back for "clarification" or "re-scoping." The instinct is to add more people downstream.

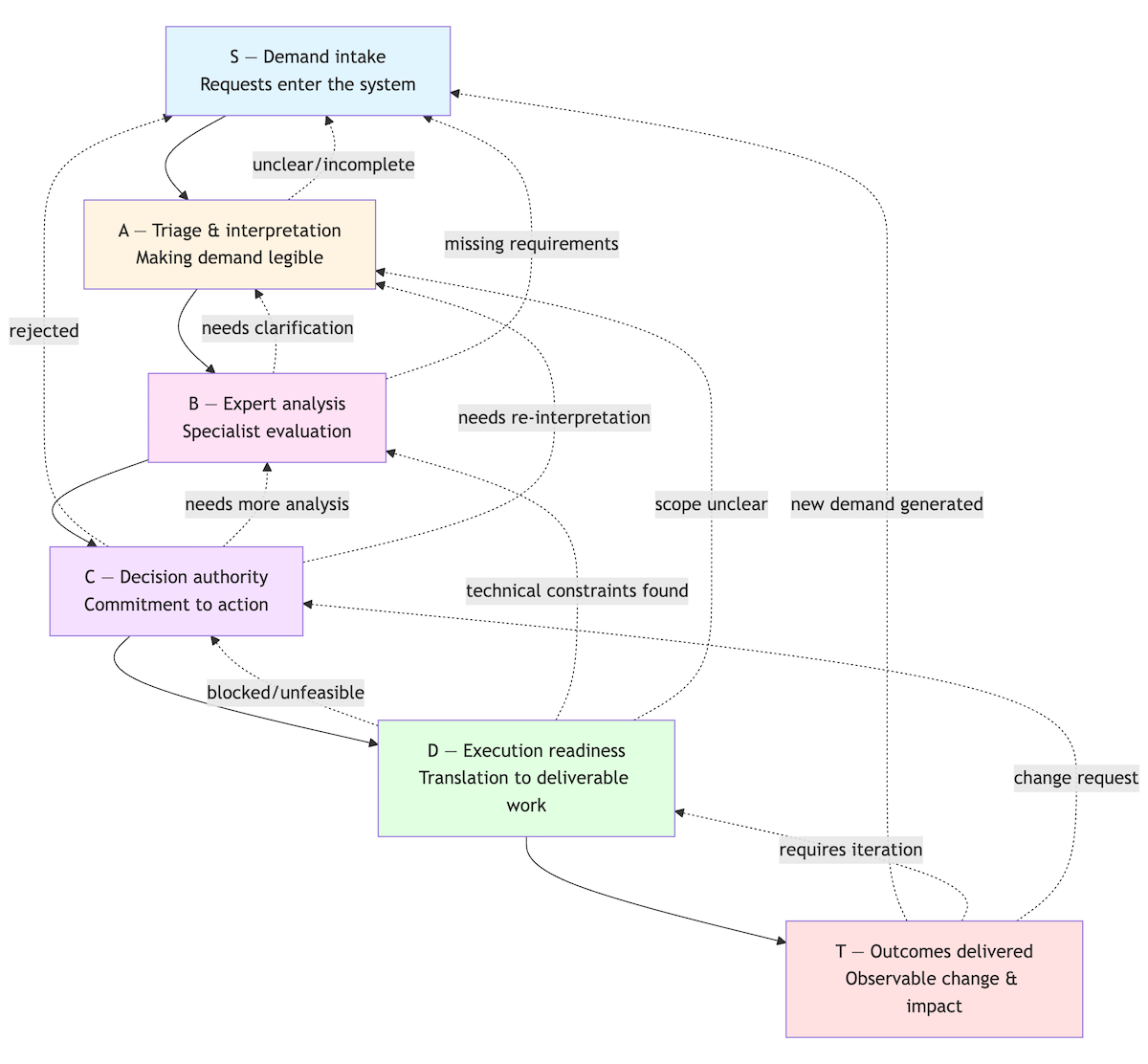

I modelled this as a six-stage workflow: demand intake → triage → expert analysis → decision → execution readiness → outcomes delivered. The surprising result was not that a bottleneck formed, but where it settled.

When decisions fail to resolve meaning, priority, or feasibility, work gets sent backward for clarification or re-thinking. These feedback loops pile up work at the decision stage, no matter how much capacity you have downstream.

Even when I varied capacity by ±20–50%, the main bottleneck stayed at the decision stage (moving from stage C to D) in 61–67% of runs. Earlier stages sometimes became bottlenecks, but only temporarily. This wasn't because decisions were slow, it was because they didn't resolve things. Unclear requirements upstream and real-world constraints downstream kept forcing work back through the decision stage, concentrating the load there no matter how fast delivery teams worked.

The insight was this: The system keeps asking the same question again because it never answered it properly the first time.

At this point, speeding up delivery does little. More execution capacity improves local flow slightly but doesn't change how the system behaves. The real leverage sits in decision-layer structure: specifically, how decision authority gets broken up, sequenced, and resourced.

Rather than repeating this point throughout, the rest of this article treats it as established and focuses on why it happens and what fixes it.

When “decision” fragments, optimisation becomes a search problem

The core modelling mistake is treating "decision" as one thing. In practice, decision authority gets split across incompatible criteria that interact in messy ways. When you break it down explicitly, three distinct decision types appear:

Meaning / Interpretation - What are we actually building? What does "done" mean? This resolves unclear intent and scope, and is the only authority that can force fundamental re-definition.

Priority / Funding - Is this worth doing now, compared to everything else? This allocates scarce resources and is the only authority that can reject work outright.

Feasibility / Delivery - Can this actually be done within real constraints? This validates whether work can be delivered given time, budget, dependencies, and available capacity.

These are not organisational roles. They're decision types. Critically, they don't commute: the order matters. Resolving priority before meaning produces different outcomes than the reverse. Feasibility constraints can reopen interpretation, which in turn reopens priority.

Different work types stress different authorities:

Unclear but valuable work stresses Meaning

Clear but resource-constrained work stresses Feasibility

Politically mandated work stresses all three at once

Once you make this structure explicit, several things become clear.

Why intuition fails

Isolated fixes fail. Reallocating capacity or changing routing policies alone both underperformed baseline. Over-investing in one authority without aligning the others increased churn and reduced throughput. Routing discipline without matching capacity just moved queues around.

Only combined changes work. Improvements only appeared when capacity allocation and routing policy were adjusted together. Rules without capacity shifts load; capacity without rules speeds up rework.

Effects are non-linear. Small changes interacted in ways you couldn't predict locally. What looked like a management problem behaved like a search problem.

This is the point where intuition breaks down. Once decision authority fragments, the system is no longer fixable through incremental tuning.

The search I actually ran

I fixed the total decision making budget at 24 capacity units per week (it’s divisible and asked a concrete question: how should those units be distributed across the three decision authorities?

A capacity unit represents a fixed amount of decision attention per week (for example, person-hours or formal decision slots). A churn event happens when an item fails to resolve at a decision authority and gets sent backward for re-work.

I evaluated:

55 valid capacity allocations (in steps of two, respecting minimum staffing)

32 routing policy combinations (five binary switches; three policies fixed by governance)

1,760 configurations, each simulated ten times

In total, 17,600 simulations, scored on throughput, lead time, churn, and pathological “stuckness.”

Performance varied non-linearly across combinations of decision authority capacity and routing policy. The best configuration was far from intuitive balance, and couldn't be reached through isolated capacity or policy changes.

The results were decisive:

Configuration | Throughput | Lead Time | Churn | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Balanced Baseline | 0.93 items / week | 32.6 weeks | 1.69 / item | 1.36 |

Capacity only fix | 0.62 items / week | 35.0 weeks | 1.78 / item | 0.89 |

Policy only fix | 0.63 items / week | 33.3 weeks | 2.54 / item | 0.80 |

Best combined | 3.71 items / week | 3.6 weeks | 0.67 / item | 5.41 |

The best configuration: 14 units to Meaning, 4 to Priority, 6 to Feasibility, paired with specific routing rules was far from intuitive balance. Yet it reduced churn by ~60% and more than halved lead times, producing a fourfold improvement in overall performance.

This improvement was structural, not incremental.

Why this becomes a quantum-shaped problem (and why that matters later)

At this point, the optimisation problem had a clear structure:

Discrete capacity allocations

Binary routing policies

Hard constraints

Multiple competing objectives

This defines a search problem with discrete choices (aka combinatorial), not a smooth landscape. Exhaustive classical search was feasible at 1,760 configurations. It won't scale gracefully. The question isn't whether we can search this space, but how long brute force remains viable.

As the number of decision authorities increases, the configuration space grows exponentially. Exhaustive classical search only works at small scales, motivating structured sampling approaches once problem definition is complete.

The quantum step was introduced not for speed, but to test whether the problem structure itself, once defined correctly, mapped to quantum optimisation approaches. Using candidate reduction, a one-hot formulation, and QAOA sampling, the algorithm concentrated probability on near-optimal configurations as circuit depth increased.

This doesn't prove quantum advantage. Classical enumeration was faster here. The relevance is structural: once organisations scale to more decision authorities, more work types, and finer-grained capacity, exhaustive search becomes impossible. Sampling methods that exploit structure become valuable only after problem definition is complete.

Quantum computing does not fix bad problem definition. It only becomes useful once the problem has been framed correctly.

What this means for organisations

Decision structure is architecture. Treating decision authority as one homogeneous thing hides the main source of congestion. Meaning, priority, and feasibility are distinct types whose interaction determines system behaviour.

Execution speed is rarely the binding constraint. In this model, upstream and downstream capacity were deliberately non-binding. Outcomes were driven by decision sequencing and resourcing, not delivery pace.

Who decides, and in what order, matters more than how fast teams execute. The difference between intuitive balance and structural alignment was a fourfold improvement.

Once decisions fragment, you're already in a search problem. Most organisations run these searches implicitly, on intuition. Making them explicit reveals leverage that intuition misses.

That's what optimising before quantum advantage actually means: structure the problem so well that optimisation, classical or quantum, has something meaningful to act on.

Forward question:

If your organisation's throughput has stalled, is the constraint really execution capacity, or is it unresolved decision authority cycling back through the system?

This article is part of the "Quantum Optimisation Before Quantum Advantage" series.

Key Terms

Decision Convergence: Whether a decision produces a stable outcome or forces work back into the system for "clarification" or "re-scoping." Non-convergent decisions create rework loops that dominate throughput loss.

Decision Authorities: Distinct decision types that don't commute (order matters). Meaning/Interpretation (what are we building?), Priority/Funding (is this worth doing now?), and Feasibility/Delivery (can this be executed?) interact in complex ways, resolving them in different orders produces different outcomes.

Churn: The number of rework events per completed item. High churn indicates the system is processing the same work repeatedly rather than resolving it the first time.

Capacity Allocation: How decision-making resources (person-hours, authority bandwidth) are distributed across different decision functions. Balanced allocation (8-8-8) underperforms asymmetric allocation (14-4-6) when authorities interact.

Routing Policy: Rules that determine how work flows between decision authorities; for example, "meaning-first" (resolve interpretation before priority), "fast-lane" (skip priority review for feasibility-cleared work), or "one-touch interpretation" (prevent rework loops).

Combinatorial Search Space: An optimisation landscape where solutions are built from discrete choices (not continuous variables), creating a space that grows exponentially with problem size. Can't be solved by traditional methods.

QAOA (Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm): A quantum algorithm designed to sample from complex choice landscapes by concentrating probability on high-quality solutions. Used here to demonstrate problem structure, not to claim speed advantage.

Interaction Effects: When changing two variables together produces results that differ from the sum of changing each independently. In this model, capacity allocation and routing policy interact, neither alone improves performance, but combined they deliver 4x improvement.

Stuckness: Items trapped in endless loops where they cycle between decision authorities indefinitely without resolution. A failure mode distinct from slow processing or high churn.