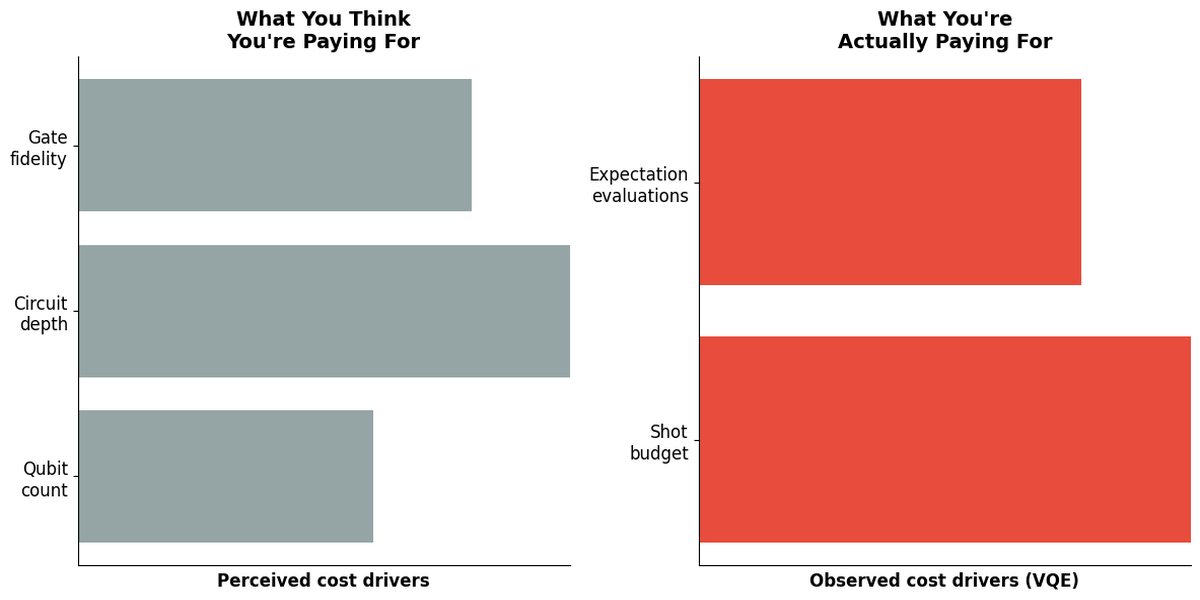

For near-term variational algorithms, the dominant cost drivers are repeated expectation evaluation and shot budget. Circuit complexity and qubit count contribute far less than most intuition suggests.

Here’s the TL:DR…

Before running optimisation algorithms on quantum hardware, you need to understand what actually dominates cost and where performance breaks down.

This article examines a deliberately constrained Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) run on real superconducting hardware to establish three things:

(1) that the optimisation behaves as expected under ideal conditions but rapidly becomes sampling-limited under finite measurement,

(2) that repeated expectation estimation dominates QPU time and cost long before circuit depth, qubit count, or gate fidelity become limiting factors, and

(3) that the resulting error is driven by measurement variance and orchestration overhead rather than algorithmic failure.

The value is not demonstrating optimisation performance. It is establishing economic interpretability. This is the step that determines whether near-term quantum optimisation results are meaningful, comparable, or scalable at all.

Unfamiliar terms? Jump to the Key Terms section at the end.

VQE on Real Quantum Hardware: What Actually Dominates Cost

In a previous article in this series, I used Bell and CHSH tests to establish something narrow but important: that a real superconducting quantum processor behaves quantum mechanically at all. Entanglement survived contact with hardware. Non-classical correlations were measurable.

That work answered a necessary question, but not a useful one.

Once quantum behaviour is established, the more pertinent question is not what can be done next, but what dominates when that behaviour is used operationally.

Variational Quantum Eigensolvers (VQE) are an obvious place to look for the answer. They are the canonical near-term workload: hybrid, noisy, and built almost entirely around repeated expectation estimation. If there are structural limits to near-term quantum optimisation, they should appear here first.

This article is not an attempt to extract the best possible energy from a molecule. It is a deliberately constrained stress test of what dominates when a theoretically sound quantum workflow is executed under real conditions.

The deliberately small experiment

The problem is intentionally minimal.

Task: Estimate the ground-state energy of molecular hydrogen (H₂).

Logical size: Two qubits after reduction.

Hamiltonian: A fixed six-term Pauli sum.

Ansatz: A shallow, hardware-efficient circuit with one repetition and eight parameters.

Optimisation: A conservative iteration budget.

Execution: Open access to real hardware, with no batching and no sessions.

Mitigation: None.

The Hamiltonian is a sum of six Pauli terms (II, IZ, ZI, ZZ, XX, YY) with coefficients fixed by molecular geometry. For H₂ at equilibrium bond length, these coefficients are well known from standard quantum chemistry. The exact ground-state energy is −1.915 Hartree.

This is not an approximation. It is the full electronic Hamiltonian after qubit mapping.

Nothing here is tuned for performance. There are no adaptive ansätze, no term grouping, no error mitigation, and no extended optimisation runs. Those constraints are deliberate. The goal is not to demonstrate what VQE could achieve under ideal engineering, but to observe what dominates when it is run as-is on real hardware.

Establishing the ceiling

Before touching hardware, I ran the same Hamiltonian and ansatz on an exact statevector simulator. The result converges cleanly to the known ground-state energy to numerical precision.

This matters because it establishes a baseline. Algorithmically, there is no problem to solve. Any deviation that follows is not a flaw in the formulation.

Sampling already dominates the economics

Before hardware noise enters the picture, finite sampling already changes the character of the problem.

Running the same workflow under a finite shot budget produces apparently strong results very quickly. Best-of-run energies dip impressively during optimisation.

Those results do not survive validation.

Re-evaluating the best-found parameter settings at higher shot counts exposes the bias. The optimiser is chasing statistical fluctuation rather than a stable minimum. The validated energy is higher, but consistent.

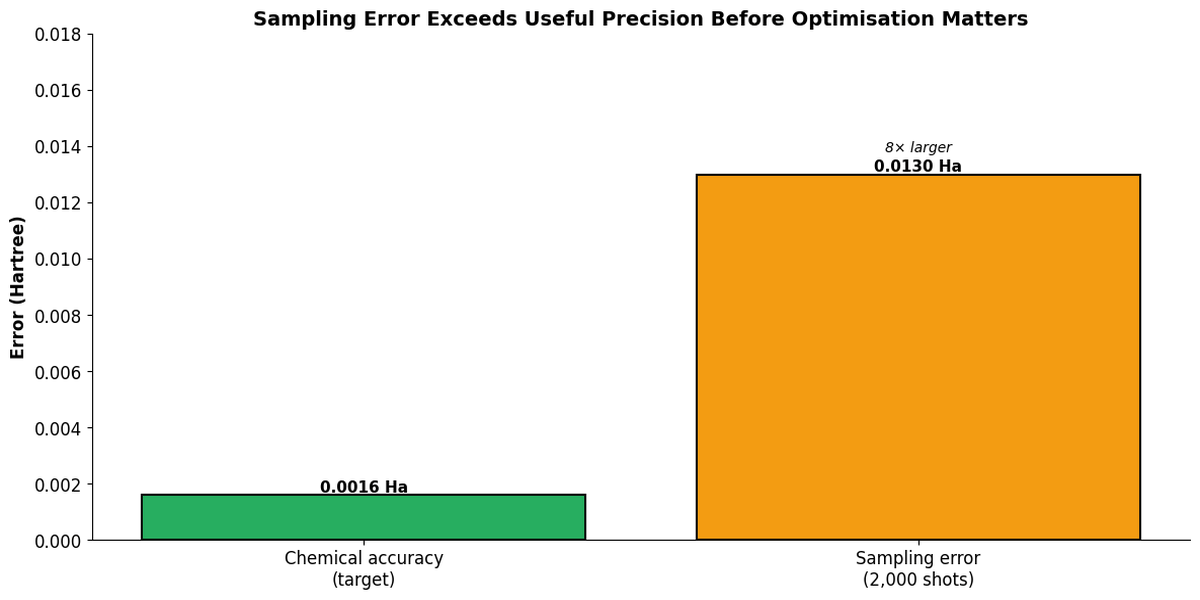

At 2,000 shots per expectation evaluation, sampling error is approximately ±0.013 Hartree. Chemical accuracy, the threshold where quantum chemistry predictions become useful, is roughly ±0.0016 Hartree. The optimiser is not finding minima within that tolerance. It is fitting noise.

At realistic shot counts, statistical uncertainty exceeds the precision threshold where optimisation improvements become meaningful, making repeated measurement the dominant constraint.

This is the first structural lesson. Without explicit validation, VQE results are systematically misleading under sampling noise. Best-of-run values are selection artefacts, not estimates. This effect appears before hardware noise becomes relevant.

Hardware reality: representation before physics

The most important hardware effect is not noise, but representation.

A two-qubit circuit does not remain a two-qubit object. After transpilation, the runtime represents the circuit at full device width, in this case across a 156-qubit backend, even though only two physical qubits carry operations.

This is not an error. The runtime schedules, validates, and prices jobs based on the full device representation because observables, layouts, and execution metadata must be consistent across the target backend. Cost follows representation rather than logical intent.

This is a reminder that near-term quantum workloads are shaped as much by orchestration and execution models as by circuit physics.

The hardware run

The hardware experiment mirrors the constrained setup used earlier.

Same Hamiltonian

Same ansatz depth

Same shot budget

Conservative optimisation loop

The result is straightforward. On hardware, the optimisation trajectory descends rapidly at first, moving from approximately −0.4 Hartree to around −1.7 Hartree over the first ten iterations, before flattening.

The shape of the curve matters more than the endpoint. Early descent exists, but progress slows quickly as sampling variance and noise dominate. The final measured energy of −1.680 Hartree corresponds to a 12.3% error relative to the exact value, roughly 150 times chemical accuracy.

This outcome is expected under the imposed constraints. Finite shots, no error mitigation, a shallow ansatz, and conservative optimisation are sufficient to explain it. Validation confirms the system reached its effective limit rather than producing a statistical outlier.

The bill

By this point, energy values matter less than counts.

Total shots: 34,000

Expectation evaluations: 16

Active qubits: 2

Two-qubit gates: 1

Circuit depth: 16

QPU time: approximately 3–4 minutes of billed runtime, spread across multiple short jobs

Wall-clock time: significantly longer due to queueing and orchestration overhead

Each shot produces a single measurement outcome. Each expectation estimate requires thousands of shots to reduce variance. Each optimisation step requires at least one expectation estimate. The measurement cost compounds multiplicatively.

This is why VQE cost scales with iteration count rather than circuit depth (see article header image). Even trivial circuits become expensive when they must be measured repeatedly, one evaluation at a time, through a real service interface.

What dominated, and what did not

Across simulator and hardware runs, the same pattern appears.

Dominated:

Expectation estimation frequency

Sampling variance

Runtime orchestration and job granularity

Lack of batching or session reuse

Did not dominate:

Ansatz expressibility

Logical qubit count

Circuit depth

Two-qubit gate complexity

These are accounting facts rather than subtle performance effects.

What would change the economics

This experiment also makes clear which interventions would matter.

What would help:

Batching expectation evaluations to reduce orchestration overhead

Session-based execution, where multiple evaluations share runtime context

Reducing the number of distinct expectation estimates through grouping or reuse

What would not:

Deeper ansätze without reducing measurement count

More aggressive optimisers that increase evaluation frequency

Marginal gate-level improvements without addressing workflow granularity

These are not algorithmic breakthroughs. They are economic ones.

Implications for near-term optimisation

VQE behaves as advertised. It descends, stabilises, and produces physically meaningful estimates on real hardware.

What it does not do is escape the economics of measurement and orchestration. Any near-term optimisation workflow built on repeated expectation estimation inherits these constraints. Improvements in ansatz design or optimiser choice matter, but they are second-order compared to how often expectation values must be measured and how that work is scheduled.

Claims that ignore the time and cost of repeated expectation evaluation are incomplete.

Conclusion

The progression from Bell tests to VQE is not a march toward advantage. It is a diagnostic sequence.

Bell tests establish that entanglement survives contact with hardware. VQE reveals what dominates when that behaviour is used operationally. Today, that constraint is the cost of repeated measurement and orchestration overhead.

Repeated measurement and orchestration time are the limiting factors. Optimisation efforts that do not account for this constraint are misdirected, regardless of algorithmic sophistication.

This article is part of the Quantum Optimisation Before Quantum Advantage series. Code and supporting artefacts are available in the accompanying repository.

Key Terms

VQE (Variational Quantum Eigensolver): A hybrid quantum-classical algorithm that estimates ground state energies by optimising a parameterised quantum circuit to minimise the expectation value ⟨H⟩ of a Hamiltonian. The quantum computer prepares states; the classical optimiser adjusts parameters.

Shot: A single execution of a quantum circuit resulting in one measurement outcome (a bitstring like |00⟩ or |11⟩). Thousands of shots are required to estimate expectation values reliably under sampling noise.

Expectation Estimation: The process of measuring ⟨H⟩ by preparing a quantum state, measuring in appropriate bases, and averaging results over many shots. Each VQE iteration requires at least one expectation estimate; complex Hamiltonians require many.

Sampling Variance: Statistical uncertainty arising from finite measurements. With N shots, standard error scales as 1/√N. At 2,000 shots, this uncertainty (~±0.013 Ha for H₂) exceeds chemical accuracy requirements by an order of magnitude.

Chemical Accuracy: The precision threshold (±0.0016 Ha or ~1 kcal/mol) where quantum chemistry predictions become useful for real applications—predicting reaction rates, binding energies, or molecular properties reliably.

Hamiltonian: A mathematical operator representing the total energy of a quantum system. For molecules, it's encoded as a weighted sum of Pauli operators (I, X, Y, Z) acting on qubits after qubit mapping from electronic structure.

Ansatz: The parameterised quantum circuit structure used in VQE. Its form determines what states can be prepared, how many parameters must be optimised, and how deep the circuit becomes—but ansatz complexity doesn't determine measurement cost.

Validation: Re-evaluating optimised parameters at higher shot counts to distinguish genuine minima from statistical fluctuations. Without validation, optimisers systematically overfit to noise, producing misleadingly low "best-of-run" energies.

Orchestration Overhead: The non-quantum time costs of submitting jobs, queueing, transpilation, result retrieval, and scheduling. For small circuits with many evaluations, orchestration can dominate wall-clock time even when QPU time is minutes.

Session-Based Execution: A runtime mode where multiple jobs share context and device reservation, reducing per-job overhead compared to submitting each expectation evaluation independently through the public queue.

Measurement Bill: The total cost (in shots, runtime, and budget) of repeated expectation estimation. The fundamental economic constraint of variational algorithms—independent of gate fidelity or qubit count.